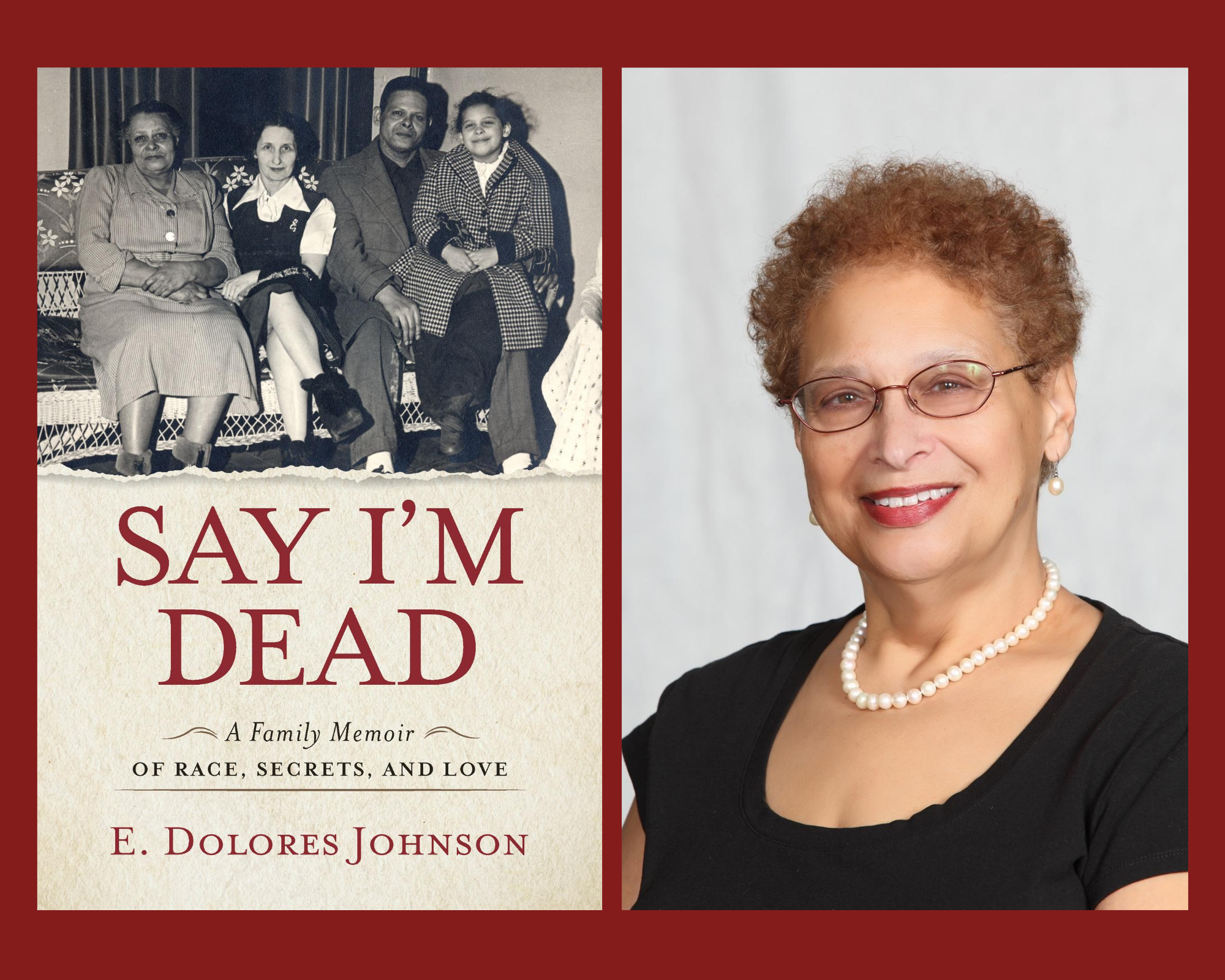

Pangyrus Nonfiction Editor Artress Bethany White interviewed E. Dolores Johnson, author of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets, and Love (Lawrence Hill Books, 2020) to learn more about her memoir and the tragedy of racism in her family history.

Artress Bethany White: Let me start by saying that I really enjoyed reading Say I’m Dead. In your memoir, as you worked through themes of lynching, economic oppression, and racial discrimination—themes that pervade the African American literary tradition—what kept you feeling that your story was worthy of being told amid so many others?

E. Dolores Johnson: The themes of lynching, economics and discrimination are the truth of my family and Black life in America and are vividly portrayed in scene after true scene of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love. The book also deals with the related theme of racism levied against interracial families. In my family, we lived with both kinds of racism, because we have five generations who lived in mixed-race relationships. And that is the uniqueness of this story, that and the portions told from my white mother’s point of view differentiate Say I’m Dead from so many other books in the canon.

The part of this memoir that people gravitate to is the escape of my white mother and Black father from the 1943 Indiana Klan culture to marry legally elsewhere and hide from Mama’s family for 36 years. Yet the beginning of my family’s mixed relationships, as in all such relationships in America, began in slavery. In the 1800s, my 15-year-old great grandmother was repeatedly raped by a white man on a plantation. I believe Say I’m Dead is a narrative worthy of being told because it stands on the truth of racism yet has a hopeful note when decades later the puzzle pieces of the two sides of my family, and the two sides of myself, come closer together through love. By the two thousand-teens, my Black daughter did what her grandmother never could: marry across the race line without fear. And now my mixed-race grandson is part of census statistics: the growth in mixed-race births outstrips the birth rate for single race babies three-to-one. Yet he must be trained on the racist dangers he will face in America and his role in defeating them. This is, therefore, not the oft-told tragic mulatto story either.

ABW: In your memoir, you poignantly recount being told that college was not for you by your white high school guidance counselor. Thankfully, you were offered and able to accept a full scholarship to Howard University and went on to earn a Harvard MBA. Under your guidance, your daughter attended both Brown University and Princeton. Do you believe that African American students continue to face a level of educational discrimination in this country similar to what you faced in the 1960s?

EDJ: Only through the serendipity of a neighbor telling me to take the scholarship exam for Howard University did I get a college education. Until then, higher education was a closed door to me, a girl whose guidance counselor never looked at her transcript of honors classes, yet said Black girls “don’t go to college.” Hers was a racism that directed me to take up other women’s hems for a living, even though I’d botch every one of them since I got a D in sewing. Winning that four-year, fully paid Howard scholarship changed my life. There, not only was I educated in economics, but the history and issues of Black America. It was the place that gave me the intellectual foundation and personal confidence to go on to Harvard and an executive career. It was the drive for educational success passed on to my daughter. Unfortunately, my experience with that counselor in Say I’m Dead has been similarly recounted by many others. In Becoming, Michelle Obama’s 1980s counselor tells her she is not Princeton material, so shouldn’t apply. And yes, this discouragement continues today, according to a 2017 article in Education Next, where Johns Hopkins reported that “… white teachers, who comprise the vast majority of American educators have far lower expectations for Black students than they do for similarly situated white students.”

ABW: One of my favorite and most compelling sections of your memoir is when you transition from your husband’s illness in the aftermath of the cross-burning incident in your front yard in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the mid-1970s to the childhood event of your parents purchasing their first home in Buffalo, New York. You write deliberately about redlining and the exploitation of Black homeowners. Recently, I found myself considering that home ownership in all-white neighborhoods is proof of the performative nature of liberal white allyship separating political discourse from praxis. I am curious about your thoughts on this assessment considering the experiences of you and your family.

EDJ: My family was devastated by the destruction of the beautiful parkway that attracted us to buy in that certain neighborhood across town from our ghetto. The parkway was replaced within a few years of our arrival by an Expressway. It accommodated the white flight people who didn’t want to live near us, moved to suburbs, and then had long commutes that inched through rush hour. In Say I’m Dead, this disregard of our newly achieved homeownership was but one way that whites maintained de facto segregation across America. The cross burning at my newly purchased Baton Rouge home was another.

Sadly, America’s housing remains segregated. Ninety percent of suburban residents are white while many urban areas are majority minority. To my mind, that is a cornerstone of racism’s continuing life. Segregated housing means segregated schools, which means different races have little opportunity to know each other and form relationships that can overthrow underlying stereotypes, fear and doubt.

Once established in my career, I chose to live in white suburbs for two reasons: better schools for my child and rising property values. One of my white neighbors expressed surprise at my economic and educational standing among them, which signaled a lack of understanding of Black success. We all got along. But when HUD proposed affordable housing in that town, people fought it, not understanding the motive to make teachers and first responders able to afford to live there. As to allyship, the question is not whether some whites have the intention of learning about racism, but what are they willing to give up to eradicate some of it.

ABW: In the latter third of your memoir, you compare the lives of your white ancestors to that of your African American forebears. You note that, “My maternal grandmother was raised by a striving craftsman who chose to immigrate to America for a better life, plying his trade freely in the late 1800s while my Black sharecropper great grandmother was being raped by a plantation white man.” You use these situational and economic realities to graphically depict the historical economic inequity between white and Black Americans. How do you see an acknowledgement of this history ending “opportunity privilege” in this country?

EDJ: Thanks for calling out that passage. I wanted readers to understand the root of today’s inequities, back to that real 1800s difference in my own family. Those who have read that section of Say I’m Dead have yet to comment on it. Feedback thus far has been an overall condemnation of the racism my family experienced, but I’m afraid acknowledgement of racial inequities will not end “opportunity privilege!” At this current moment of racial reckoning, America is only beginning to know the history and impact of inequities. Knowing precedes acknowledging, which precedes actions that can change the status quo.

ABW: As I read your book, I thought about my own literary journey to discover more about my family’s American enslavement and white genealogical ancestry. When I tested my DNA, I ended up being of 28% European ancestry, yet for me to claim myself as a white citizen would be ludicrous on multiple levels, starting with the fact that I am a brown-skinned woman. When you carried out your own DNA test, you tested 75% European ancestry. Do you attribute your grounding in your African American selfhood as a combination of a more realistic acceptance in the Black community of a history of enslavement leading to a logically diverse color palette as well as a devotion to your more brown-skinned father and his race experiences in America?

EDJ: Throughout American history, people mixed with Black and white have been considered Black. That started with slavery too, when Massa fathered mixed offspring; he counted them as additions to his slave holdings, not family. Hence the Black community is still where mixed people are included and comfortable, rather than white ones. Though DNA says I am 75% white, I, like in Caroline Randall Williams’s New York Times article, “…am a confederate monument.” What tips my DNA into mostly white is my great grandfather, the plantation rapist, whose blood repulses me. What has formed my dominant identity is both the racism my family and I endured and my four years at Howard University where Black pride, achievement and activism took root in my purpose.

ABW: Once you understood that your parents’ marriage was a secret one, your memoir becomes largely about finding your white relatives as a means of coming to a better understanding of your biracial identity. Was it your desire that readers walk away from reading about your journey with a surety that embracing difference carries fewer pitfalls than holding onto traditionalist racial baggage?

EDJ: After learning so much by tracing my father’s genealogy, I felt the hole in me from not knowing anything about my mother’s half of my heritage. The idea of biracialism wasn’t on the table in 1979 when I searched for them because there was no permission to be half white in America. There was no telling what reaction her family would have when I showed up. The beauty of my story is that the fear, secrets and separation my parents lived with because of systemic racism did not hold up on the personal level when we found Mama’s white family. So, I embraced my white family, my half who decided love trumps race. Say I’m Dead shows America can bring the races together, though I cannot assure you of how that will happen or what the price of getting there will be.

____________

E. Dolores Johnson is the author of Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets, and Love (Lawrence Hill Books, 2020), a multigenerational memoir that shows America’s changing attitudes toward mixed race through the courageous journeys of the women in her family. Dolores was born in Buffalo, NY. She earned degrees from Howard University and Harvard Graduate School of Business in Boston. Johnson is a published essayist focused on inter-racialism. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To learn more about her and her work, visit her website www.edoloresjohnson.com or follow her on Twitter @e_dolores_J, Instagram @edoloresjohnson and FB Dolores Johnson.

![]()

Artress Bethany White is Nonfiction Editor at Pangyrus and the author of the poetry collection My Afmerica (Trio House Press, 2019), and the essay collection Survivor’s Guilt: Essays on Race and American Identity (New Rivers Press, 2020). Her prose and poetry have appeared in such journals as Harvard Review, Tupelo Quarterly, The Hopkins Review, Pleiades, Solstice, Poet Lore, Ecotone, and Birmingham Poetry Review. White has received the Mary Hambidge Distinguished Fellowship from the Hambidge Center for Creative Arts for her nonfiction, The Mona Van Duyn Scholarship in Poetry from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and writing residencies at The Writer’s Hotel and the Tupelo Press/MASS MoCA studios. She is associate professor of English at East Stroudsburg University in Pennsylvania and teaches poetry and nonfiction workshops for the Rosemont College Summer Writers Retreat.

On Race, Secrets, & Love: An interview with E. Dolores Johnson

June 22, 2021

E. Dolores Johnson is an essayist, memoirist, and former tech executive who consulted with universities and corporations on diversity and inclusion. Her debut book, Say I’m Dead: A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love, was published by Chicago Review Press in June 2020. In the last year, her memoir won the National Association of Black Journalists’ Outstanding Literary Award, received a starred review from Booklist (American Library Association), was included on Powell’s Black Lives Matter Reading List, and was cited in Publisher’s Weekly as providing a bounce for small press sales during the Spring 2020 market.

Johnson and Sonya Lea, author of Wondering Who You Are, first met at the Tin House Summer Workshop, where Dolores was writing Say I’m Dead, and Sonya was writing essays on whiteness and racism in relationship to the last public execution in America, a legal lynching in her hometown in Kentucky.

Over the past year, the two connected again to discuss Johnson’s memoir.

Sonya Lea: In 1943, your Black father and white mother were terrified by a local lynching and the mandatory prison time exacted for violating Indiana’s anti-miscegenation laws. So they fled, married, then lived in hiding for decades. Your parents chose love over the law 24 years before Loving vs. Virginia’s 1967 win at the Supreme Court. You woke up to the absence of your mother’s family after you began your father’s genealogical search, in your adulthood. How did hearing your parent’s story impact you? Were parts of their story closed to you?

E. Dolores Johnson: We lived with no mention or knowledge of my mother’s white family for 36 years. They simply did not exist in our consciousness. It seemed normal and sufficient that we had a (Black) family. Until I caught the roots craze and did my father’s genealogy. Once I stood back from the resulting large chart of generations of relatives, it struck me that the only white person there was my mother. That could not be right. Where were the branches on her family tree?

Only by confronting my parents in an emotional family weekend did they finally tell me, at age 31, that they ran away and disappeared without ever contacting her family again. And they were still afraid, 36 years later, that the law would come after them. My identity as a Black woman tilted, hearing about the family she left behind, realizing my white half had never been acknowledged. I had to know what that meant in me.

SL: You begin the book with a detailed description of the emotions you experienced while being required to code-switch to accommodate whiteness and white work environments. You interrogate yourself thoroughly on the page, noting: “The thing was, leaning into white culture had gotten to a point where I wondered if maybe I was selling out. Like fitting in and enjoying the other side diluted the Blackness that always defined me. I had to get out of this halfway house and get back to me. But how?” Was writing this story one of the ways you authenticated this experience? What was the moment you knew you were going to write this book?

EDJ: For me, writing memoir means honestly examining significant happenings that provoke changes in your life. The theme of identity is key to Say I’m Dead, for me and other family members. Performing behaviors acceptable to white people was exhausting, having to filter out my natural speech and body expressions. This is something very familiar to Black people who work in white environments, something whites don’t realize or ever have to do themselves. This is the authentic truth and writing Say I’m Dead was not necessarily a reckoning of this truth as much as an explanation for white readers.

I once worked at a journalism institute, where I picked up on ways to document stories. In talking with one journalist about my background, she agreed to interview my mom on tape when she was in her 90’s, to capture her story in her own words. Considering that recording was the moment I started writing this book.

What do you mean by “authenticating experience?”

SL: That’s what I think of as the writing process getting close to the lived experience. Or of the craft used to convey the experience

is as close to the quality of the experience possible. When I was writing my memoir, and when I sent it into the world, I had a sense of trying really hard to convey how beautiful it was to live in my relationship with my husband, though there were these tragic and difficult moments. But perhaps I should say that I wanted to write the relationship as complicated as it was. I’m thinking here of what Maggie Nelson talks about when she says, “I like to think that what literature can do that op-ed pieces and other communications don’t do is describe felt experience…the flickering, bewildered places that people actually inhabit.” And so I’m asking how the process of writing the scenes, of finding the language, of detailing the emotional and lived truth might have been a way of getting to the reality of this complex story?

EDJ: I worked to put the truest representations and feelings of my and my family’s lived experiences on the page. It was an effort to tell the unvarnished truth so the reader got an authentic understanding. It wasn’t as much a craft technique as it was my tendency to very direct language and the need for the reader to stand in my shoes.

SL: The story of investigating your mother’s family, the white mother who had to escape the systemic racism of her hometown in order to be with the man she loved, became one of the ways you sought the truth. This was incredibly powerful in Say I’m Dead because your mother had created a way of leaving that included making her family presume she was dead. Why do you think you were the one to do this work?

EDJ: When my mother finally told me her story the first time, she raised her chin a bit defiantly and said, “I left my family and never meant for them to find me. And they never did.” It was mind blowing, trying to come to terms with what she had done. Not only was it necessary to channel her emotions, the love, the anxiety, the fear, the sorrow she had in leaving behind a family that loved her, but it took a lot of research to understand the conditions in Indiana at that time. The record showed what my parents told me: it was too dangerous to be with the man she wanted to have a family with. There had been a lynching of two Black men in Indiana, partially because a white woman claimed rape, and after they were dead, she said it never happened. In 1943, openly affiliated Klan members sat on the Indianapolis city council, who would have readily enforced the prison time for her crossing the race line.

You ask why I was the one to do this work. Some would say I was the risk taker in my family, the first to go to college, the one to break corporate ceilings, the one to move to Europe. My older brothers chose different paths – one a committed race man who dedicated his life to teaching inner city kids, the other living a low-key life with a white wife on the white side of town. Neither of them felt the same pressure I did from the daily shift of my identity from privately Black-centered to white corporate work. I had to clarify for myself what the dual heritage meant to my identity, while they felt more settled in who they were.

SL: Considering the stance of your mother – you say she “never had the woe‑is‑me talk about mixed‑race prejudice. Instead, she modeled how to let such “foolishness” roll off our backs as best we could.” Did speaking about the mixed-race prejudice in the book break any family codes?

EDJ: My family all understood mixed-race prejudice because we lived with it every day. People called us names, said insulting things, recoiled in horror at the site of us together. Beat up my brother for looking too white, caused my mother to hide her husband’s race to keep her job, and so much more. In 1958 when my parents had been married for 15 years and I was 10, PEW Research did a national poll and discovered that 96% of Americans thought race mixing was wrong.

Yet, my mother was concerned most about what we ourselves thought. We were a well-knit family who looked out for each other. We did not have any issues of our own about being mixed race. It was other people who could not understand that people of all races were the same in their desires, needs and spirits. What Mama did was treat and accept everyone the same and show us how not to take society’s racism into our own hearts.

SL: In your memoir, there are also terrifying stories of the racial violence you endured, including when white people threatened your life. You were born in 1948, and throughout your life, you endured many racist roadblocks and aggressions. You lived for a time in Louisiana, where you had a cross burned on your lawn. As an adult, when you searched your father’s genealogy, you found out that your grandmother was the product of a plantation rape. You and your family lived the changes our country continues to wrestle with, and which are so very apparent in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, and previously in Ferguson.

It’s such an impactful story you’ve told here, including the ways the police interacted with your family, and the ways that influenced you as a child. You say, after one encounter with your family stopped by a police officer: “The police had rendered my powerful father a timid subservient in front of us, because he had a white woman. They disrespected Mama for having a Black man, skipping any normal courtesies given white women. Because she was only a sort‑of white woman.” You’ve also included your daughter and grandchild as the next generation in this memoir, including the ways they must deal with the resurgent bigotry of this time. I know you were active in the Civil Rights Movement in the sixties, and I’m curious about how you see what’s taking shape now, for your family and the community. Do you envision your writing and community as continuing the work of your ancestors in fighting for collective freedom?

EDJ: The historic sweep of racism’s impact on five generations of my family was an intentional story arc for Say I’m Dead. The theme of how racism has impacted us in so many forms from 1890 when my great grandmother suffered multiple plantation rapes to my parent’s secret marriage during Jim Crow, my troubled need to understand my mixed identity and my daughter’s fears today about her son’s possible police encounters is meant to illustrate how deeply seated racism is and always has been in America.

The racial protests following George Floyd’s death erupted from another historic thread. White authorities have abused Black bodies without consequences dating back to slavery beatings and continuing on to stop and frisk ordinances and today’s vigilante and police killings. On so many fronts, in housing, education, employment, economics and income the racial disparities continue to plague our country. There is much work to do in the fight for true equality and freedom, and people, Black and white, have got to keep up the fight. My own intention is to keep writing works that give Americans insight on what it’s like to live on the Black side of the line.

E. Dolores Johnson’s debut book, Say I’m Dead, A Family Memoir of Race, Secrets and Love, was published by Chicago Review Press in June 2020. Her essays have appeared in Narratively, the Buffalo News, Hippocampus, Pangyrus, Lunch Ticket, and elsewhere. Johnson completed Grub Street’s year-long MFA-equivalent Memoir Incubator, and attended summer writing conferences at Bread Loaf, Voices of Our Nation, and Tin House. She was awarded writing residencies at VCCA, Blue Mountain Center, Ragdale and Djerassi. Johnson is a former tech executive who has consulted with universities and corporations on diversity and inclusion. She holds a BA from Howard University and an MBA from Harvard University Graduate School of Business. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (@e_dolores_j)

Sonya Lea’s memoir Wondering Who You Are(Tin House) about what happened after her husband lost the memory of their life, was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award, and won Seattle’s Artists Trust Award. Wondering has won awards and garnered praise in a number of publications including Oprah Magazine, People, and the BBC, who named it a “top ten book.” Her essays have appeared in Salon, The Southern Review, Brevity, Guernica, Ms. Magazine, Good Housekeeping, The Prentice Hall College Reader, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Rumpus, and more. Lea has worked as a house cleaner, a cook, an editor, and for museums and science centers. She creates retreats and teaches writing in North America. (@sonya_lea)

Writing on Race: In Conversation with E. Dolores Johnson

by Elizabeth Solar

Long before we curated the Acts of Revision site, we wrote together as a group called ‘Write Where We Are’. We can’t underestimate the level of support and encouragement we give each other. It has paid off. One of our WWWA writing tribe published her first book. Today we’re talking to E. Dolores Johnson, fearless WWWA member and author of Say I'm dead, A FamilyMemoir of Race, Secrets and Love, published June 2 by Chicago Review Press.

Dolores has additionally published essays on mixed race, racism and identity. Find out more at a edoloresjohnson.com. We spoke with Dolores two weeks ago. Here’s the first of our three-part interview where we cover writing about race, publishing in the time of Covid, and writing memoir.

AoR: Hey Dolores, thanks for talking with us today. Congratulations on the book.

EDJ:Thank you very much. Yes, the book has been out in the world six weeks, and I'm very excited. It's getting some good coverage in the media and lots of appearances have happened. So, I hope this audience will enjoy our discussion about it and the issues that are embedded in the story.

AoR: Your memoir is a family odyssey of race, love and courage. It traces the story of your black father and white mother, who fled Indiana in the 1940’s because interracial marriage in that state was illegal. You follow four generations of females. But one figure that looms large in your book is your dad. I'd love you to read a passage from the book that talks about your dad and the challenges of being a black man in the United States.

Read the excerpt at the end of this post.

AoR: Thank you, Dolores.

EDJ: I want to say that the story centers also on my mother. My mother was white, and my father was black. The scene is one where, as an adult, I'm reflecting on the racism that my family dealt with. Racism, because we were black and racism, because we were a mixed-race family. [The incident in the passage] takes place in the early 50s. And it's interesting to note that in 1958, the Pew Research Center did a study that showed that 96% of Americans were against race mixing.

AoR: We’ve seen some progress, but we have a long way toward racial equality and acceptance. The timing of your book’s release: a week after George Floyd's murder, a few days before the 53rd anniversary of the Loving decision, which struck down state laws against interracial marriage. Then, a few weeks ago, the death of John Lewis, one of the last surviving civil rights leaders of the 1960s. We’re experiencing parallels to the protests of the 1960’s, leading to the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Yet, there’s still so much misunderstanding, particularly among white people, about racial identity. As children, were you and your siblings aware of what that mixed-race relationship meant to your entire family?

EDJ:Yes, because we were constantly abused because we were mixed race. My father was abused, and I was abused and my brothers were abused because we were black. And [there was] the ‘one drop rule’ in the United States, the informal designation that says if you have one-drop of black blood, you are black.

We were black people, but we were also mixed-race people - as I mentioned earlier - and so we had a double whammy, if you will, as far as racism is concerned. My father was unable to rent a decent place for us to live because people didn't rent to black people. We lived in a flat in the second house on a one-family lot, one-house lot and we lived pretty much in darkness because we were overshadowed by big buildings. [Our house] was heated by a potbelly coal stove.

AoR: That potbelly stove figures into an early memory of racial bias based on your zip code. Tell us about that.

I fell against a red-hot potbelly stove when I was a small child and burned my arm very badly. The skin rose up like burnt meringue off my arm. And we didn't have a car. My parents called a taxi and explained that it was an emergency to take me to the hospital. And we waited on the sidewalk in the frozen winter of Buffalo, New York. And nobody ever came. Later on, my father had to call around to people who had a car to see if someone would take us to the hospital. And he said that the cab didn't come because the white cap company wouldn't come to the black neighborhood.

There were so many occasions when my father would come home from work and he would be livid because he was the only black person in his shop. While he was a master welder, they treated him like some lower underling. He never got his correct title or pay and was, you know, subject to the word ‘nigger’ all the time at work. As we grew up, we experienced people who would see our family and shove their children far way, so they wouldn't touch us, who would spit near us…speak nasty things intentionally in our hearing.

AoR: I want to address the issue of slavery because I read something in your book that speaks to the interracial relationships between master and slave. You have some lineage, some experience with that within your own family history.

I was doing my father's genealogy, so I went south to meet my Great Aunt Willie …We were looking through pictures, and she was telling me who these people were and how they were related to each other. We were building this genealogy chart on her dining room table and she pulls out a picture of my grandmotherat about the age that I was when I went for this visit. She holds up the picture and she says, “Well look at that. You and your grandmother are the spitting image of each other because you know, you both have that white side.”

I said to her, “What white side are you talking about?” She said, “Your grandmother's father was white. You don't know that?” And I said, ‘No, I've never heard that.’

[My great-grandmother] worked on the plantation where all the ancestors were slaves and was raped by a white man on the plantation. I was so revolted. To imagine my great grandmother, who…must have been about 15 being repeatedly abused by this man, and my grandmother being the issue of that. And I said, “Well, my Grandmother must have beenashamed. That's why she's never spoken of that to me.” My great aunt said, “Well, why would she be ashamed? She didn't do anything wrong. That's what white men have always done to black women, and there's nothing we could do about it.’

So yes, there's a plantation rape in my background. And as [African American historian and scholar] Henry Louis Gates has stated - because he's done tremendous work around the mixing of races in America - that the very blackest-looking African American in America is still 12% white. That's why I say every African American shares that audacious history.

AoR: The one drop rule is so insidious because it negates everything else that you are as a person. In a more perfect world race would be something that, you know, could be as incidental as the color of your eyes, or your IQ, or personality quirks. It could just be one other thing about you. Yet so much attention has been paid to blackness. Do you find that there's now a bit more clarity [among white people] about what it means to be black or interracial in this country?

EDJ:The one drop rule…was actually codified. If you look at the US census records, which I have studied all the way back to 1790, you see that the classification of people is, first of all, the category of race. This is the mentality about America that's been embedded in our psyche all along. There were black people and white people. Then there was a category called mulatto, which is half black and half white. But mulattos were slaves, because the slave masters were raping the slave women. That's how mixed-race people appeared in United States - from slave rapes. But the masters had their own children out in the field as slaves, giving them no benefit of their paternity.

…The federal government has been a party to this one drop mentality all along. Now we have a census that has offered a category where you can actually check off and self- identify as multiracial. And 2000 was the first time that I was able to honorably recognize my white heritage and my black heritage.

AoR: How did you finally come to terms with your own mixed heritage?

It wasn't until I looked at [my father’s geneology] chart of generations of black people that I actually had a light bulb go off. That my mother was my white family all by herself. She had nobody else on that genealogy chart. And that wasn't right. She had to be from somebody, somewhere.

AoR: Having written this book and considering what's going on in our country right now, are you leaning towards the hopeful side, or the skeptical side of things?

EDJ:I look at the overall trajectory of race in America. And by that, I mean I've been a student of African American history all my life and starting from slavery through reconstruction through Jim Crow through the civil rights movement. I was an activist and remain an activist in a number of ways. I see that changing America's mindset on race is a very tall order. And so many thought it would be conquered during the civil rights movement in the ‘60s, and that more doors would be open, and progress made. I think that we have been inching towards more social justice in this country, but we have a very long way to go.

AoR: A much longer conversation, and one we will continue. In the meantime, what can we do to build a bridge between white people and people of color?

EDJ:There's lots of books* and articles available, but also by talking to and interacting with black people. An opener could be something with people that you work with, who live in your area, who you cross paths with. To say to them I, you know, I haven't been as aware before as I would like to have been, to understand what it is to have a black life in this country. And I wonder if you would talk with me about it. And if you get a positive response to have a conversation, the number one rule is for you to listen.

[You can] back policy changes and politicians who are going to change things like police policies and working to stop voter suppression… If we can have advocates in the legislature, and in key political positions, who will help make these changes, there's a much better chance to see things change… People can also advocate for revised American history lessons in schools …It's time to start teaching that to children…Think about mentoring minority children… making space for other people in your neighborhood, in your jobs, in your schools.

AoR:So, start with a conversation. Really listen. And engage. One more question. Having done all of this work and soul-searching, do you embrace your white side, in the same way you have your black?

I met my white family the expectation of racismand [those feelings]vanished because they were much more concerned with a loving family relationship than they were about race. And after my mom was reunited with her sister, we had 26 years [together] before these two passed away.

I still am in touch with my cousins.

And there's an understanding that I received through not only my mother's, but my relatives’ example about what family means, what relationships mean, and how the construct of racism …can be taken out of the equation and we can just be people together. And we can love each other.

To prove that we now have so many more interracial marriages in this country than we used to. [the US Census] shows the growth rate in birth of mixed-race children now outstrips the growth rate in single race children by three to one. So, I think a lot of people are understanding what my family came to understand: that race is not important. Family is getting along and loving people and giving people the humanity that you want given to you is really what matters.

AoR:Dolores, thank you so much for spending time to share your story. Continued success with the book. We’ll meet up next time to talk about publishing in the time of COVID.

EDJ:Thank you, delighted to be your guest today.

*Dolores book recommendations - So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo, How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi, White Fragility, by Robin DiAngelo

Writing Memoir: In Conversation with E. Dolores Johnson

August 14, 2020

by Elizabeth Solar

Note: This is the second of a three-part interview with E. Dolores Johnson’s author of ‘Say I’m Dead’ a multi-generational memoir about growing up in a multiracial family after her black father and white mother fled Indiana’s severe anti-interracial marriage laws in the 1940’s. Her book was published this past June.

AoR: Last week we spoke about race as it relates your book, and this moment in the United States. Let’s talk about the story itself. When did you know that you wanted to write this as memoir?

EDJ: I began my writing attempts after I concluded my corporate career. Having written so much material as an executive, I sat down and just wrote this in the same manner that I had always written.

AoR: How did that go?

EDJ: My work material, which is everything is due yesterday, so this got to be, you know, tight and not verbose. I gave it to a writing teacher who gave it back to me and said, ‘You know, what you have here is not a story. It's a business report. So, you need to learn how to write creative writing because you don't know anything about it.’

I initially took classes in Novel Writing, but I didn't want to exaggerate the characters in the way that fiction usually demands that you do. Because I wanted to tell the truth and I didn't want to offend my family and I switched to a memoir, because I thought that was the best way to tell the story.

AoR: Were there any relatives or other people close to you, perhaps your mother who discouraged you not to write the book? Was there opposition to it?

EDJ: Well, my mom and I talked about the material in this book for years, and she knew I was going to try to write it. We had been over all the emotional ground in prior discussions when I start writing, but the one person who I was quite concerned about was someone I grew up with, [whose mother was ] in a club that my mom and some lady friends had started to call the ‘Clique Club’. That was a group of white women in Buffalo that were all married to black men. Most of the women were Italian, married to black jazz men, and they were all Catholics. My mother met them by taking my oldest brother to enroll in Catholic school where she ran into another white woman with a brown child.

AoR: What ejection did that friend’s family have?

EDJ: One of the members of that club lead a double life. She was married to a black man, but she told her family back in Ohio that she had a very hectic job in Buffalo. She, you know, needed to stay in Buffalo, but she would come home for visits, and she often went back to Ohio for Easter and birthday parties and Fourth of July cookouts and the like. Always hiding the fact that she had a black husband and three black children.

I went and talked to that family having included their story in the book because I wanted to show the extremes that people had to go to in order to marry across the race line.

The daughter of that family who's my age was very reluctant. And she didn't really want that story told, but she had two older brothers who said that they thought I should write it. And they voted…The brothers prevailed. So that story went in.

AoR: Now that the book’s been published, what is that family’s reaction?

EDJ: … [the daughter of] that woman has called me and praise the book to high heaven and said she's so glad that I wrote it. So, she was not offended, even though at first it was touch and go. And this woman's mother went to the grave with that secret.

AoR: Your mother’s friend never told her white family about her husband and children?

EDJ: When she became ill at the end of her life, she was living in her daughter's house. And her people in Ohio were worried about her and wanted her to move home, so they could take care of her. She invented this story that she was going to get a caretaker to live in with her. That was her own daughter in her own house, who had to answer the phone as if she was a caretaker, passing information back and forth. And this woman called her three kids together, and she said, ‘I don't have long left. What I want you to do, these are my final wishes, is send my body back to Ohio and let me be buried with my white family. In my maiden name, and you are not to come to the funeral, I don't want the secret exposed.’ And then she took it [the secret of her family] to the grave.

AoR: That takes my breath away. It must have been so emotionally painful. As you continued to investigate your family’s background, what type of emotions came up for you?

EDJ: I cried a lot over the keyboard. I'll confess that upfront, because even though I had come to terms with much of what happened in my family, there's layers to that. And when you're writing you want to channel other people's feelings and actions, try to understand them and portray them truthfully, empathetically.

You have to dig, so very deep. You really have to isolate, to write that deeply. And so there was a lot of clenching in my stomach. There were times when I was angry times, and I had to come to terms with forgiveness. This is a very emotional ride.

AoR: We all tell stories about our lives, whether they are published or not. And we tell those stories from our own point of view. Sometimes depending on where we are in life, that often changes how we frame things. You had two brothers. If they had the chance, how do you think either one of them would have written this memoir or told the story?

EDJ: I had two older brothers, David and Charles Nathan, who were quite different. I would explain their personalities as fight versus flight. David was a black militant. He wore dashikis all the time. He chaired the Juneteenth festival decades ago, [before it was more widely recognized by the mainstream] and he was very outspoken. He spent his life in service to inner city kids as a sixth- grade teacher. And he cared about those children deeply. And so, you know, he was a person who would stand up and speak about racism, and American history and really invest in the success of inner-city children. David would have probably written a different memoir, which was the glowing history of inner city black people.

Whereas my oldest brother, we suspected at times, passed for white. He was the whitest- looking among us. He married a white woman. They lived on the white side of town. It wasn't that we didn't see him. But it seemed that he never volunteered his racial history. When he died, the only black people at his funeral were my daughter and I, and a couple of other black people that I asked to come. I don't think my oldest brother would have written anything, because he was a person who wanted to stay out of the fray. As he told me, ‘I just want people to leave me alone.’

AoR: So, you all had very different experiences. Sounds on par with what happens in most families. Let’s shift to your research. And this will blow a lot of people’s minds, especially younger people. You didn't have a lot of information to work with to find your mother's family. Tell us how you tracked them down.

EDJ: In my 30s, I actually had a light bulb go off that my mother was my white family all by herself. She had nobody else in her genealogy chart [that I drew up]. And that wasn't right. She had to be from somebody, somewhere.

She had been missing for 36 years, [from her home state of Indiana] so I had no information to start looking for her family. [My mother] and my dad gave me enough information, and I took this class at a community college, which was on how to trace your family history. So, I took a week off from work and went to Indiana. And it was all shoe leather and paper and pencil work to try and find her family. I searched vital records. I searched city directories. I made phone calls to people in the county whose names are possible match. I read all the marriage licenses for 10 years to try and find my aunt and had nothing except my grandfather's death certificate. [to go by]

But it was the church that actually gave me the connection. I'd been trying to reach the parish where I know her family worshipped, thinking that there'd be birth and death and marriage and baptism records that might give me a lead and I couldn't find the priests. I couldn't get any information. I left numerous messages and as I was leaving Indianapolis with just that death certificate of my grandfather, and the assumption that [my] grandmother had also died because there was very poor record-keeping back in those days. I called the priest from the airport in a phone booth. [as I was leaving]. [He answered] and he said I found your aunt's marriage record.

[My aunt] was married here at the church. She had married a GI during World War Two in California. So, I'm thinking ‘how I am supposed to find somebody in California now?’ But I looked in the [telephone]directory. That's when we had paper directories hanging off chains in phone booth. And there was the man's [her uncle’s] name. And that was the connection that helped me find that family.

AoR: So, [you successfully researched] without the benefit of the Internet, and ancestry.com and all these other electronic ways that we have to dig up information instantly.

EDJ: After I had taken that [genealogy] course, and I had gotten enough information for my parents to know what I was looking for, I went out [to Indiana], and it was in the course of that week that I actually made the connection to the priest and got the name of my aunt's husband.

AoR: An incredible odyssey, Dolores. It speaks volumes about your commitment to finding, and telling your story, not to mention your devotion to your mother.

on the uploaded document.

on the uploaded document.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

General Document Comments 0