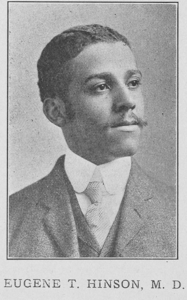

All About Dr. Eugene T. Hinson

http://Nunery, L. (2023, September 10). Eugene T. Hinson (1873-1960). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/eugene-t-hinson-1873-1960/

Eugene T. Hinson was one of six founders of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, the oldest African American Greek Letter Fraternity in the United States. The others were Henry Minton, Algernon Jackson, Edwin Howard, Richard Warrick, and Robert Jones Abele. Eugene T. Hinson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on November 20, 1873. He attended the Octavius Catto Public School, which was located on 20th & Lombard Streets. He, like other Fraternity founders, also attended the Institute for Colored Youth, which is now Cheyney University. At the Institute, he excelled scholastically and athletically, particularly in baseball.

Following graduation from the Institute in 1891, Hinson taught in Hartford County, Maryland. He then returned to the Institute for Colored Youth, where he taught in its high school. Teaching, however, was a pathway to his real ambition, the practice of medicine. Eugene Hinson entered the Medical Department at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with his M.D. degree in 1898 with honors. Hinson’s desire to secure an internship in Philadelphia hospitals, however, was thwarted by racism, and he accepted a position at Douglass Hospital, a small 20-bed institution that was recently established to provide medical services to Philadelphia’s African American residents.

Dr. Hinson left Douglass Hospital in 1905 and joined the founding group of the Mercy Hospital Corporation. This was a groundbreaking achievement as the Mercy Hospital staff would be the first in the city to be racially integrated. Mercy Hospital opened in February 1907. Dr. Hinson led Mercy’s gynecological department, and his considerable skills as a surgeon led to him having a significant practice with both Black and white patients.

Eugene Hinson was active in the Lombard Central Presbyterian Church, where he attained the distinction of Leading Elder—the highest post for a layman. As further testament to his varied interests and involvements, he was a member of the National Medical Association (the predominantly Black physicians’ professional organization) and the newly racially integrated American Medical Association, the largest professional physician’s organization in the U.S. as well as its constituent societies. Dr. Hinson was a pioneer member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, and the Alumni Association of the Institute for Colored Youth.

Another example of Hinson’s foresight and dedication to education, especially for African American youth, was his donation of some of his family farm property in Oxford, Pennsylvania, to help found Lincoln University.

Eugene T. Hinson was married to Marie Hopewell, and for most of their lives, the couple lived at 1333 South 19th Street in Philadelphia. They had no children. Archon Hinson died at his home in Philadelphia on June 7, 1960, at the age of 86.

https://findingaids.library.upenn.edu/records/UPENN_BATES_PU-N.MC78

In the late 19th century, healthcare revolutionaries, Dr. Nathan F. Mossell and Dr. Eugene T. Hinson, worked to overcome the ill treatment of African Americans by establishing a healthcare system that served to adequately train African American health professionals, and fairly provide treatment to patients. Dr. Mossell founded the Douglass hospital in 1895 to create opportunities for African-American “physicians and young women desirous of nurse training.” A decade after the establishment of Douglass Hospital, talks began amongst Dr. Hinson and other community members regarding the development of an additional institution “where the young physicians might have the greater opportunity for development.” In 1907, Dr. Hinson, together with a supporting community, inaugurated Mercy Hospital, and eventually appropriated state aid for its operations. However, not long after beginning operations, in 1931, both Mercy and Douglass Hospitals faced deep throes of a financial crisis. In 1938, first talks of a merger between Mercy and Douglass Hospitals were initiated. A decline hospital administrators’ morale stimulated thought on whether merging Mercy and Douglass Hospitals’ clinical and administrative efforts would result in better health care related services for the African-American community. Following the establishment of Mercy Hospital’s Reorganization Committee in 1940, committee members presented strong points in support of the merger between Douglass and Mercy hospitals. The hospitals were merged in March 1948, with Dr. Wilbur B. Strickland, a former army hospital administrator, serving as the first Medical Director of Mercy-Douglass Hospital. Consequently, the merger resolved the problems experienced by both hospitals in 1948.

Dr. Nathan F. Mossell, the first African American to graduate in medicine from the University of Pennsylvania, met with African American doctors and a small group of Philadelphia citizens on June 25, 1895, and conceived the idea “of a hospital where [African American] physicians might have an equal opportunity to practice, where [African American] patients could be cared for, and where [African American] nurses might be taught the art of healing the sick.” The Frederick Douglass Hospital and School for Nurses opened its doors for service on October 31st, 1895, in “a private three story dwelling” at 1512 Lombard Street. Dr. Eugene T. Hinson, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School’s class of 1898, joined the Douglass Hospital staff in 1898, with the aligned objective to create opportunities for “[African American] physicians and young women desirous of nurse training.” Before attending medical school in 1894, Dr. Hinson spent two years teaching, first at Gravity Hill in Maryland, and then the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia. After graduating from medical school in 1989, Dr. Hinson was refused entry into the University, Philadelphia General and the Presbyterian Hospitals internship programs, “even though [he] was an honor student, a taxpayer and a Presbyterian.” Nonetheless, Dr. Hinson’s professional shortcomings stimulated spirit behind the Episcopal Divinity School’s proposal for Douglass staff to acquire their site at 50th Street and Woodland Avenue as one of the properties during the hospital’s expansion. Douglass hospital continued to grow, and in 1908, acquired two more properties at 1522-34 Lombard Street. Dr. Hinson became a member of the Douglass board in 1900, and held his tenure as a board member for five consecutive years. A decade after its opening, Douglass hospital set up new departments, and increased its patient number, year by year. In 1909, the Board of Managers at the Douglass Hospital decided that its financial condition was good, and constructed a $100,000 building at 1532 Lombard Street. Despite Douglass Hospital’s financial progress, in around 1920, the hospital’s failure to meet basic requirements resulted in Douglass Hospital’s de-recognition by the Philadelphia Federation of Charities. Furthermore, in 1927, Douglass Hospital lost its endorsement for nurse training. However, in the latter part of the year, Douglass Hospital still erected a new nursing, despite not meeting regulatory standards. Two years later, in 1929, Douglass Hospital had also been dropped from the state’s accredited list recognizing training schools for nurses, and was only “conditionally approved by the American College of Surgeons with respect to meeting the minimum requirements of a Class-A hospital.” In the 1930s, Douglass Hospital faced deep financial challenges that constrained their ability to provide affordable healthcare services. The hospital had to decide, after several years of operation in financial deficit, to “curtail the treatment of free patients.” The first few years of the 1940s showed more promise for Douglass Hospital’s future. Following Dr. Douglass Stubbs appointment as Medical Director of Douglass Hospital in 1942, Douglass Hospital was re-endorsed by the American College of Surgeons, and newly endorsed for preceptor resident training. Furthermore, in 1942, the Community Chest of Philadelphia acknowledged Douglass Hospital for attempting to cooperate with the proposed Merger with Mercy Hospital, and permitted the institution, on June 1st, to join the Chest to receive its first annual grant. However, Douglass Hospital’s progress was short-lived as the hospital failed to meet basic requirements set by the Pennsylvania State Board of Medical Education and Licensure, which subsequently removed the hospital from the list of approved institutions for interne training. In 1948, the Douglass building no longer served of purpose since the merger of Mercy and Douglass Hospital - the Douglass Hospital’s building closed, and operations remained at Mercy Hospital’s site.

In 1905, Dr. Hinson left the board of Directors at Douglass Hospital, and, with the help of other community figures, began laying plans for “a new “progressive” hospital” that would “provide young physicians with a greater opportunity for development than what was offered at Douglass under Dr. Mossell.” On December 1905, a group of Douglass physicians met to reorganize a new progressive hospital, and acquired a private dwelling on the Northwest corner of 17th and Fitzwater Streets. In 1907, Mercy Hospital opened its doors for service, and, within the first few months of operation, appropriated state aid. In 1908, there was a significant shortage in Mercy hospital’s inventory of medical supplies. Furthermore, the hospital’s financial conditions made it impossible for administrators to pay hospital employees, and meet other capital-related financial obligations. In 1912, Mercy Hospital set to expand operations, and was approached by the Episcopal Divinity School at 50th Street and Woodland Avenue regarding the possibility of using their site as a new location for Mercy Hospital. Mercy Hospital purchased the west Philadelphia building in 1919 for $130,000, expanded the Nursing School, and established an Interne Training Program. The Mercy Douglass Board of Managers made an attempt to increase the community’s awareness of Mercy Hospital by instituting a series of community based lectures on health and sanitation in various churches. While Mercy Hospital experienced financial difficulties in the 1930s, it solicited funding from the Rosenwald fund through a success fundraising campaign, which made it possible for the hospital to construct a new modern home for nurses. By 1931, Mercy’s Hospital’s Nursing School had increased student enrollment to forty. In 1940, Mercy Hospital established a reorganization committee that presented strong arguments in favor of a merger with Douglass Hospital. Mercy Hospital initially rejected the proposed merger in interest of harmony. The board of Directors took another vote on March 1941, and repudiated the merger on the grounds of avoiding a “divided” and uncooperative environment. Dr. Henry M.Minton, who led Mercy Hospital as the Superintendent, resigned after twenty five years of service. The hospital’s reorganization committee decided to abolish the office of Superintendent, and divided the affairs of the hospital into a Business Administrator and Medical Director. In 1946, Mercy Hospital received a $50,000 gift from Mr. Lessing Rosenwald “to tide it [Mercy Hospital] over its difficulties.” Following the merger of Mercy and Douglass Hospitals, Mercy Hospital’s site remained operational, and housed the merged institution.

The first talks of a merger between Mercy and Douglass Hospitals were initiated in 1938, in attempt to find a solution towards fulfilling the large financial obligations of both Mercy and Douglass Hospitals. Doctors Russell F. Minton, Douglass Stubbs, and Arthur H. Thomas embarked on acountrywide tour to visit seventy hospitals largely controlled by African Americans. They concluded the medical situation of African Americans in Philadelphia at the time was by far the worst of all cities visited, with the exception of New York. The reorganization committee at Mercy Hospital in 1940 argued in favor of the merger suggesting that it would ease financial constraints, and provide the opportunity for physicians and patients to experience better healthcare related services. In 1941, the benefits of a merger between Mercy and Douglass hospitals became evident to both African American and White communities, who fully understood Mercy and Douglass Hospitals as institutions that provided opportunities for African American physicians and nurses. In 1946, a joint committee representing Mercy and Douglass Hospitals, as well as the Community Chest was established to investigate the idea of a merger. In July 1946, Dr. Eugene Hinson, one of the original founders of Mercy, was against the idea of a merger, and asked that the merger attempt be dropped. However, in 1947, the joint committee published their findings on the idea of a merger, and recommended Mercy and Douglass Hospitals merge to avoid financial instability, and eventually, closure. Mercy and Douglass Hospitals merged in March 1948, and was named the Mercy-Douglass Hospital. In addition to the merger, a group of notable physicians from teaching institutions were invited to aid the hospital in developing an adequate training program for residents, which led to Mercy-Douglass’ affiliation with the Children’s Hospital for pediatric training, Temple and Jefferson in radiology, and the University of Pennsylvania in surgery. The merger subsequently resolved the problems experienced by both hospitals. The school recessed from 1957 to 1958, reconvened for 1959, and then graduated its last class in 1960. Arrangements were made, however, to provide clinical training experiences for students from the Tuskeegee Institute School of Nursing and other schools which continued intermittently until the Mercy-Douglass Hospital closed in 1973.

References: Minton, R. F. "The History of Mercy-Douglass Hospital." Journal of the National Medical Association 43.3 (1951): 153-59.

Rudwick, Elliot M. "A Brief History of Mercy-Douglass Hospital in Philadelphia." The Journal of Negro Education 20.1 (1951): 50-66.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2641961/pdf/jnma00700-0072.pdf

DR. EUGENE THEODORE HINSON, a retired gynecologist and one of the founders of Mercy Hospital died on

June 7, 1960, at the Mercy-Douglass Hospital in his

native Philadelphia.

He was 87.

Dr. Hinson was the

second son among four children of Theodore and Mary

Cooper Hinson.

His parents owned and lived on the

grounds where Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, now

stands.

Dr. Hinson received his early education in the

0.

V. Catto public schools of Philadelphia, the Mt.

Vernon School of Camden and the Institute for Colored

Youth in Philadelphia which was the forerunner of

Cheyney State College.

He received the M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1898, joined the staff of the Douglass Hospital in Philadelphia and served as a member of its

Board of Directors until 1905.

He led the group which

founded the Mercy Hospital, which opened February

12, 1907, and was the first member of its Board.

He

headed the Department of Gynecology in this institution

until his health forced his retirement in 1955.

He was a co-founder of the Sigma Pi Phi fraternity

(Boule), the first of the Negro American Greek letter

fraternities, which was the brain child of the late Dr.

Henry M. Minton.

Dr. Hinson married Miss Marie E. Hopewell in 1902.

She died many years ago.

He never remarried and there

were no children.

Dr. Hinson was a distinguished civic leader and active in many professional and community organizations.

He was a life member of the Lombard Central Presbyterian Church.

Additional biographical data and record

of Dr. Hinson contributions may be found in the May

1956 issue of this Journal, p. 213, on the cover of which

his portrait appears.

He is one of the early pioneers to

whose vision and benefactions the present MercyDouglass Hospital stands as a monument.

His nearest of surviving kin are six first cousins and

three second cousins.

Phillips Hospital and visiting surgeon to the St. Mary's Infirmary.

He served the National Medical Association as vice chairman of the Surgical Section, 1941-49, and chairman in 1950.

He was also chairman of the Program Committee of the Homer G. Phillips Hospital Internes Alumni Association for many years and had been a member of its Executive Board since 1946.

Dr. Sinkler was the author of numerous scientific medical publications and had lectured before many professional organizations.

In addition to the National Medical Association he belonged to the American Medical Association, the St. Louis Medical Society, the Missouri Medical Association, the Mound City Medical Forum and the Pan Missouri Medical Society.

He was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha and Chi Delta Mu fraternities.

Dr. Sinkler married the former Miss Blanche Vashon on June 19, 1937.

To this union was born one son, William Vashon Sinkler, aged 20, both of whom survive him.

Minton RF. Dr. Eugene Theodore Hinson. J Natl Med Assoc. 1960 Nov;52(6):454–5. PMCID: PMC2641961.

on the uploaded document.

on the uploaded document.

0 General Document comments

0 Sentence and Paragraph comments

0 Image and Video comments

General Document Comments 0